Lesley didn’t land on his back this time, but only because Daiki had an arm around his waist. The ogre pulled him against his side as the summoning hall materialized around them. He felt hot as a heated iron pan, and Lesley tried not to think too hard about it as he swayed on his feet. He had to lean on the ogre to stay standing. Daiki stared straight ahead. He’d reverted to dormant form. He rested the head of his club on the nearest line of the summoning circle and waited for the light to die.

“Hello, Kiki,” he said, without blinking.

Up on her bench, the Dream Eater held two crystal balls, her face frozen somewhere between a scowl and a gasp.

She remembered to close her mouth when Daiki spoke.

“Daiki,” she said, spinning one of the globes. Lesley recognized his own, murky and lit only by a tiny spec of light. The second was more full of stars. Tiny constellations spattered the whole southern hemisphere. The rest stayed in darkness. “This is a strange move, even for you. You know I have to submit this to review, don’t you?”

“So submit it,” said Daiki, “but you know sharing names is hardly against the terms of our bondage.”

“It’s not against anything, but that one’s not exactly a nobody…” The Dream Eater seemed like she wanted to say more, but thought better of it. “Not that I’m at liberty to discuss any cases but your own. Still, you might want to tread carefully. You’re not a nobody yourself around here.”

She was a lot less shrill when talking to Daiki, Lesley noticed sourly. Daiki only shook his head. His bun had come out during the summoning. It fell to his shoulders in an echo of his beast’s form.

“The usual payment,” he said.

“Yeah, yeah,” said Kiki. She tapped both orbs. Another tiny star joined the spec in Lesley’s crystal. An even smaller star appeared in Daiki’s orb. The rest Kiki balanced in her hands, and this she blew on. It fell like a shooting star. Daiki’s hand vanished from around Lesley’s waist as he caught the light in his fist.

“Your credit as agreed,” said Kiki. “Want a guard to see you out? Might do you some good.”

“No need,” said Daiki. He turned and walked out of the circle.

Cold without his presence, Lesley found himself staring at those crystal balls, lightly spinning, before he dusted himself off, stuck his chin out, and marched after him as though he’d intended to do that all along.

“Goodness, I almost think that dreadful woman might like you,” said Lesley, as he followed Daiki out into the square. The summoning hall left no greater impression on him than his first time here, though he took more notice of the chimera guards waiting at the doors. “She didn’t cackle at you even once!”

“The magistrates are fixtures. As am I.”

“Fixtures, he says!” Lesley might have laughed. “What, do you make her lunch as well? What did she mean, anyway, about you not being a nobody—”

But Daiki stopped and held out an arm. They’d reached the steps of the square, and they were by no means alone.

Kiki had not offered the guards as formality. Zanza was waiting at the bottom of the steps, in dormant form, with a bandage around his forehead. He was by no means alone, either. The harpies were there. So was the troll. So were five goblins and satyrs, but they looked more like sightseers who’d stopped when they thought there might be a show.

“Good morning, Zanza,” said Daiki. Lesley was surprised to realize it was morning. He’d been so disoriented he hadn’t taken in the state of the sky, which was the color of spring roses and brightening fast.

“Morning, Daiki,” said Zanza. He showed no signs of moving.

“My business with you is done,” said Daiki.

“With me, sure,” said Zanza. He stepped to the side. “Eh, Gumi. You see? Like I told you.”

He wasn’t talking to the harpy or the troll. He was talking to the woman who unfolded herself behind him. As she was a jorogumo — a spider-woman — there was a lot of her to unfold.

Lesley nearly shrieked. He’d never seen a beast like her before. Some dark beasts, like ogres and chimera, could sometimes be seen in grunt positions in the regions surrounding the base of the Tower. They occasionally worked as bodyguards or a hired muscle, an acceptable darkness in the pursuit of light. A spider-woman was a creature that was really and truly of the dark realms. They lived in the shadowy wilds beneath the clouds, and had no love for any being of the light at all. There was nothing sightly about them.

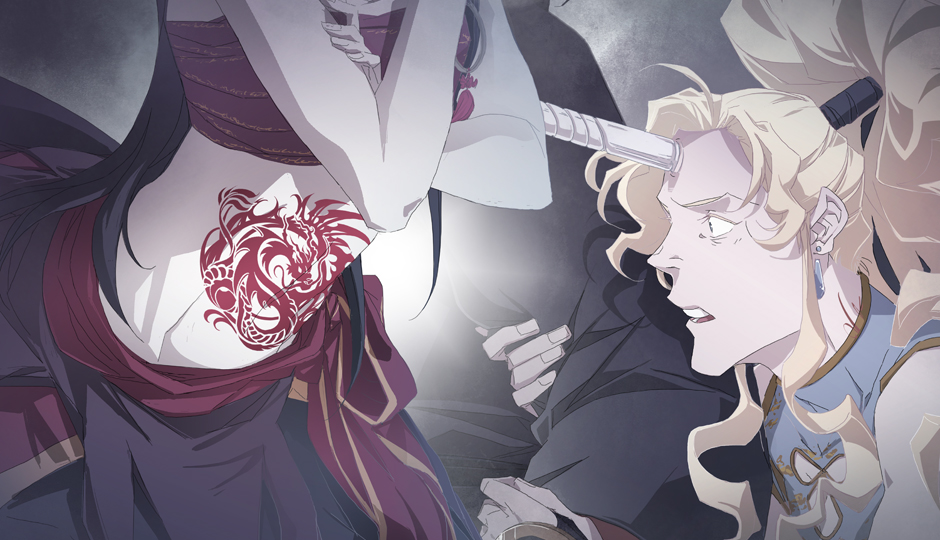

This one had not even bothered with her dormant form. Her bottom half was a horrible bobbing spider’s thorax, covered in shiny hairs and little blue specs up and down the side. Her eight legs arched up around this straining mass. Each leg was covered in more bristly little hairs, and ended in a cruel set of hooked claws. The front-most of these claws tapped the cobblestone impatiently. Her top half offered no comforts either. Supposedly, spider-women were considered deceptively beautiful. Supposedly. Lesley could find little beauty in the sickeningly white skin, offset by her limp black hair and a red slash that only barely covered her hanging breasts.

It was the red sash that caught Lesley’s eye. It had been dyed the color of blood, with gold inscription along the edge.

“Daiki,” whispered Lesley, tugging at Daiki’s sleeve. “That cloth—”

“Daiki,” said Gumi, the jorogumo. “Is it true?”

“I am not sure,” said Daiki. “What have you been told?”

‘Skrit!’ went the spider-woman’s claws across the stone.

“I have been told you have captured a unicorn,” said Gumi, “and that you are keeping him to yourself.”

“Were you told I brained Zanza in the head for being uncharitable to newcomers?” asked Daiki. “Were you told he’s been trying to give away his name?”

“I was, but that is less important,” said Gumi, waving one of her spider legs without care. Zanza made a choked noise behind her. “I am told you were summoned last night. As I see you are leaving the hall, I know that one is true, and you come out with that pretty little unicorn I am told you were keeping to yourself, so I suppose that one is also true.”

“Stop speaking like your webs, Gumi,” said Daiki.

“Webs are all we have down here. We all seem to be caught in them.”

“Daiki,” whispered Lesley, warningly. It wasn’t just that the sash that was red. He could see now that the spider-woman had the remnants of some armor over her human torso, at her shoulders a bangle hanging from her hair, and, over her human navel, carved directly into her skin, a spiralling tattoo of a red beast that had not been seen since the age of night. A dragon, wreathed in flames…

“That’s the mark of the Red Brigade.”

But Daiki didn’t seem to care about her tattoo.

“Your point?” he asked, leaning on his club.

“And since you are so occupied with your pretty new toy, perhaps you ought to turn your little kitchen over to someone else.”

“I can multitask,” said Daiki.

“I know that you can, but the question is will you? This sudden commitment to helping some little lost creature of light. Are you trying to be rid of us? Are you trying to escape us? Or perhaps curry favor? Or attention? Whose attention do you want, Daiki? You are our cook. Who will feed us if you are gone? I think we all have a stake in asking what you mean by… this?”

She gestured vaguely with her human hand in Lesley’s direction. As though he were some… thing. Lesley went tense.

“I have my reasons,” said Daiki.

“And those are?”

“None I care to disclose.”

“That is a shame to us,” said Gumi. “We really ought to. We trust you, Daiki. You offer us so much. We would hate to lose you to some bright thing, succulent though he may be. The rest of us would starve.”

“Are you asking for the job?” asked Daiki.

Gumi didn’t answer. Zanza didn’t answer. None of the onlookers said anything. One of them coughed. Another one quietly stepped backwards. Gumi rose up on her legs by about an inch, then another, her face had gone frozen with her eyes wide. She had eight of them. They were all arranged on her forehead, like a little beady tiara.

“No,” said Gumi, finally, “I am not. Why would I? I think the meals I have to offer would rather turn your stomach.”

“Then do not offer them, and if you wish for mine I would suggest you let me — and my associate — pass. Breakfast will be late as it is.”

The spider-woman made a funny clicking noise somewhere deep in her throat. She folded her human arms and shuffled to the side as Daiki pushed past her. Lesley kept close to the ogre’s side as they went. He could nearly feel the hairs on her leg as they went. She made a point of waggling her horrid abdomen when she saw Lesley was watching her.

“Such a shame,” she said. “Such a shame, Daiki. If his brightness has so captivated you, you must know he won’t put out.”

Lesley whirled.

“I beg your pardon—”

Daiki grabbed him by the back of the robes and hauled him around a corner and out of the mob’s sights.

Daiki didn’t let go of Lesley until the hut was in sight. Once they were inside, Lesley collapsed against the wall and dragged his hands down his face.

“That creature was a member of the Red Brigade,” said Lesley. He’d almost launched a spell at her. He wondered for a moment how that would’ve gone for him, then he shuddered and went back to scrubbing at his hands. He couldn’t get the memory of those bristles out of his head.

Daiki said nothing as he pulled open the curtains of the kitchen and started laying out the pots.

“Please tell me you know what that is.”

“Mm. Some troublemakers, I take it.”

“Troublemakers hardly covers it,” said Lesley. “They claim to be the direct thralls of the Archdragon herself.”

“The Archdragon?”

“Please tell me you know that—”

“I know that,” said Daiki, “but the Archdragon has been sealed for over a thousand years. Ancient history is of little concern in this place.”

“It would be everyone’s concern if the Red Brigade had their way.” Lesley pushed himself up the wall. It took some effort. The exhaustion from the summoning had started to get to him. He was amazed Daiki could stand, let alone start arranging his kitchenware. How did he do it? “They followed a demon who worshipped her. They swept across the grey realms, destroying every bit of light they could find there. They are mortal enemies to the Tower of Dreams, and of Creation itself.”

“Mm. I suppose that would get one on the lists.”

“If they didn’t choose death before service.” Lesley wrung his hands together. “I didn’t think any of them had. I didn’t think they still existed. What’s one of them doing here? And what do they want with you? Asking you — oh. You’re not one of them are you? You don’t work for them, do you?”

Lesley froze. He brought his hand over the name on his neck. He couldn’t feel the difference between the new paint and the old, but he could trace it nonetheless.

Rubedo. Red. Had he signed himself over to his people’s worst enemy?

“I don’t work for Gumi, no,” said Daiki. “If you consider the work of a common chef a service, I suppose, then, yes, I do them some favors.”

“They are a dangerous group,” said Lesley. “They despise the light, and beasts that live in it. I suppose I’m in for it with you now, but know that I cannot willingly work with one who condones such extremists—!”

Daiki draped a dish cloth over his face.

“Gumi is a hungry woman,” said Daiki, as Lesley extricated himself. “If she indulges with what I make, then she does not make prey of the smaller beasts that wind up here.”

“This had better be clean,” huffed Lesley.

“It’s clean,” said Daiki. He took the dish cloth and handed Lesley one of the leftover radishes. Lesley eyed it before chomping down on it.

“Mmfg. That is barely an excuse you know,” he said, swallowing, “but, I suppose, it is adequate, and you didn’t hand me over to her, so I suppose I must thank you for that as well… Why did you keep some of the magic we returned with?”

“I run a kitchen, don’t I?” Daiki turned one of the hotstones over. Lesley saw the symbol written in it and leaned forward.

“A dream circle,” said Lesley. “You shape it?”

“I would not get very far without ingredients. I must call them from somewhere.”

“I didn’t think ogres could even do that sort of magic.”

Daiki held out his hand. The ball of light the magistrate had thrown him glowed in his palm. He produced the pot of ink he’d used to write his name on Lesley’s neck. He mixed it in. After a second, he laid a flat sheet of paper on the circle. He took the ink, wrote a few lines of script. The circle came alive. The stone hummed. The ink bulged. The paper puffed out and folded itself into a ball. The circle’s light rose around the ball.

It popped. A fresh radish lay in its place.

“It’s possible,” said Daiki. He lifted the radish by the stem, examined it, then set it aside and laid another sheet of paper on the circle. He dipped the brush, and began to write another line. This time, he called a fresh pork cut. This he wrapped quickly and set it aside. Lesley wrinkled his nose at the stench. Daiki wiped off the stone and set down another sheet.

“Is it just one at a time, though?” asked Lesley, after watching Daiki pull forth an onion, a head of cabbage, and an egg.

“We didn’t pull much this time,” said Daiki.

“Nevertheless, this isn’t the most efficient use of…” Lesley started, then he paused. “Were you self-taught?”

“More or less.” A fish steak, this time. “Any objections?”

“It’s remarkable,” said Lesley, honestly, “for what you have on hand.”

“Hm,” said Daiki.

He called a clove of garlic. He called a chunk of ginger. Lesley shifted from side to side. He didn’t want to have opinions on it. He really didn’t, but he could see that the ink pot was already half empty. When he shifted for the fifth time, Daiki looked at him. “Would you like to try?”

“Well. Since you asked,” said Lesley. He didn’t wait for Daiki to hand the pot of ink over. He took it from him. He painted a few loops and closed his eyes.

He let his mind drift. It drifted out of this room and into the space between. The flow of ether and magic between the realm and the other places was a two-way concourse, even in a place like Coppertown.

He couldn’t go very far along that concourse, though. He couldn’t see much in the murk. The flow of dreams was more like a stifled trickle of thoughts and feelings. He could barely even hear words from the other place. In Coppertown, so close to the darker realms, the ether ran weak and dim, a leaden grey far from the brightness of the Tower and the surrounding clouds of inspiration. Still, he could pick out the light from the names he had written on the page.

It would have to do. Lesley chased that light. Lesley called to it, welcomed it. Even with such a small light to serve as a guide, even so far from the true source of inspiration, someone had once dreamed of a warm kitchen, a clean cutting block, a fresh, safe meal. Dreams of a warm meal were one of the most basic impulses of any creature in any world. Lesley picked out the first that came to him.

The glow from his horn filled the kitchen. The paper rose, folded itself over, once, twice, and then exploded in a bloom of light. Lesley opened his eyes to admire his work. He’d pulled forth a dozen radishes, gathered in a bundle and tied with a string.

Daiki picked up the bundle and turned it around in his hands. He reached up and sniffed it. The marks over his eyes creased as he raised an eyebrow. He looked legitimately surprised. He whistled. Lesley crossed his arms with a smirk.

“There,” said Lesley. “One doesn’t get to be the Second Summoner in the Tower of Creation sleeping his life away. Economy is everything, you know, even when you are crafting the stuff of dreams.”

“You will exhaust yourself,” warned Daiki. “Save tricks like that for when we are called.”

“This ‘trick’ costs me very little. It’s your ether,” said Lesley. His limbs felt a little heavy, but he had his time in the other place to blame for that. He sat back. He gave a lock of hair a little twirl, to show he wasn’t too burdened by it. “And if you mean the summoning itself, that’s nothing to me. In the Tower, I was able to call down banquets, already cooked! My means are more limited now. The natural flow of ether this far down is weaker, and, as you said, we didn’t pull much with us from the other world, but shaping some rough material into the basic ingredients you need… well. You may have it well at hand, but I might as well spare you some effort, hm?”

And, because he really was feeling charitable, he decided to pull out a pile of soybeans. So many that a few of them fell off the hotstone as they materialized. Daiki stepped away from them and stared. His nostrils flared.

“Beans,” he said.

“Yes,” said Lesley. “Is there a problem?”

“I…” Daiki couldn’t quite seem to form a proper sentence for a moment. “Why.”

“For tofu, obviously,” said Lesley. That earned him another blank stare. “That is something you can make, can’t you?”

“Yes,” said Daiki, eyeing the beans with the suspicion one ought to have reserved for an especially oily politician.

“You can’t expect me to eat burnt flesh, now can you?”

Daiki sighed and moved to sweep the soybeans into one of his bowls. They filled it to the top. He put a lid on it, set it in a corner, and stood as far away from it as he could.

“It does save me some time,” said the ogre.

“And some ether,” said Lesley. “If, perhaps, you’d prefer to keep a larger cut to yourself next time.”

“Charitable.”

“Well. You didn’t throw me to that spider,” said Lesley. “I suppose we’re both feeling charitable today. Consider this before you consider the Red Brigade again, hm? I can bring some things to the table, you know.”

“Ah,” said Daiki, and, to Lesley’s surprise, he laughed. It was a warm sound. Warmer than the hotstone. The corners of his eyes creased with it, and, despite the set in his jaw, the ogre grinned. It wasn’t entirely nasty teeth. It could even be called welcoming. “Maybe I will.”

Lesley forgot how to talk, until the ogre popped another radish in his mouth. It ruined the moment completely.

They drank muddied tea and went to bed. Daiki had found a second bedroll. Where or how, Lesley couldn’t be sure. He pretended to be too tired to ask. He almost was. Exhaustion weighed at every limb. He watched through half-lidded eyes as Daiki rolled the second one out. In the tight quarters of the hut, they barely counted as two seperate rolls spread out. Lesley laid down and the ogre laid down next to him, so close that Lesley could feel his body heat, even through the blanket. When Daiki breathed, it may as well have been next to Lesley’s ear. Each breath practically whistled through his teeth. In dormant form, Daiki’s lower jaw didn’t jut out quite as prominently as it did in his true form, but it still made for an impressive silhouette.

It occurred to Lesley then that he had never slept so close to anyone before, either in the Tower, or in the Marches where he’d grown up. He glanced at Daiki from under his half-cracked eyes. The ogre lay with his arms folded behind his head, his craggy profile easily made out in the light that filtered through the cracks in the roof. He laid with his eyes open, staring up at the ceiling, or some distant memory. Then, eventually, he grunted, turned his back to Lesley, and his breath evened out. The deep rhythm of it was almost comforting. Lesley watched his side rise and fall under the blanket.

‘You must know he won’t put out,’ the spider-woman had said.

…Of all things to remember, just then. Lesley sat up and edged out from under his own blanket. Creatures of the dark truly were lewd.

Mindful of his steps, Lesley crossed the hut. He’d started to understand the layout: kitchen in the front, folding screen in the back, chests along the walls — and what thin walls they were! Lesley could hear the night sounds of Coppertown, none of them pleasant: A cough from some vagrant wandering by. The distant screech of two dark beasts having a scrap. The sound of wings, much too close.

Lesley slipped into the kitchen. He found the hotstone propped next to the wash basin. He considered going back for Daiki’s ink, but thought better of it. No. The ogre might notice that, and the chest was likely locked. Lesley would have to do this the old fashioned way. He held his nose and picked up one of the cloths Daiki had left hanging over the basin, the ones he used to wipe the stones down when he’d finished cooking the meat.

Lesley laid the hotstone across his lap. He used the towel to trace the pattern on the circle. It took some doing. Most of the char had mixed with water. He thought again about the ink and the sheets of paper… but, no. The ogre probably counted the sheets. Lesley closed his eyes, and did his best to lose his mind to the magic.

Again, the murk of Coppertown assaulted his senses, the dreary despair that seemed to rob every individual of even a spark of inspiration. Even at night, when most of the inhabitants would have been asleep and dreaming, Lesley could find little by way of power around him. He could feel the deep thrum of Daiki’s dreams in the other room, but even that was lost in a rust-colored mist, like an old pot left in the sink too long. Lesley considered testing that particular murk, testing the ogre’s dream — but the ogre was guarded enough when awake, and Lesley was no Dream Eater, who danced around in others’ heads without a care. He had a different objective in mind.

He set his mind towards the starlight, towards the clouds, towards the Tower — the advantage of this kind of summoning was he wasn’t shaping anything physical, he was simply calling something which already existed. He placed his hand over his poorly traced symbol and let his mind carry him to the memory of a place where that symbol had once been drawn out in full, carved into the beautiful mahogany red of a fine wardrobe…

It came to him like an in-drawn breath. His head snapped back. His horn burned.

A pile of robes fell across his face.

Lesley dug himself out from under the cloth. He counted them. One, two, three… five! Five robes, all as freshly pressed as they’d been the morning he hadn’t realized would be his last in the Tower. So they hadn’t cleared out his personal quarters yet.

They’d probably already cleared out his workshop.

“Ephemera must be having fun with that one,” Lesley muttered, but he did wonder what else had been left behind.

It was worth experimenting. He’d left marks all over his personal quarters and workshop, originally for when he didn’t want to wait for one of the apprentices to bring a book from his quarters, but now it served to shorten a far greater distance.

He could try the sigil on his bookcase, or even his desk — but his eyelids throbbed from fatigue, and he thought he heard the ogre shift in the other room, so he wiped down the stone, stuffed the robes behind the folding screen, and hurried back to bed.